during the “great leap forward,†what were peasants encouraged to produce in their backyards?

China's Swell Leap Forward

Download PDF

From 1960–1962, an estimated thirty million people died of starvation in China, more than whatever other unmarried famine in recorded human history. Most tragically, this disaster was largely preventable. The ironically titled Great Leap Forward was supposed to be the spectacular culmination of Mao Zedong'southward programme for transforming Cathay into a Communist paradise. In 1958, Chairman Mao launched a radical campaign to outproduce Great Britain, mother of the Industrial Revolution, while simultaneously achieving Communism before the Soviet Matrimony. Just the fanatical button to meet unrealistic goals led to widespread fraud and intimidation, culminating not in tape-breaking output but the starvation of approximately one in twenty Chinese.

Too few Americans are enlightened of this epic disaster, and even among the Chinese, information technology is not well-understood. In the involvement of informing a full general readership of both the facts and lessons of the Keen Spring Forrad, the following article outlines the disaster, offset with Red china's successful, centralizing reforms of the early 1950s; Mao's subsequent devolution into a paranoid despot as he purged critics and fostered a blind, fanatical devotion to his own naïve policies; and how this spiral ultimately ravaged the Chinese population. Nosotros conclude with a comparison of this famine to others and, finally, the lesson that this harrowing experience offers in the dangers of suppressing critical, contained thought.

Mobilizing the Masses

Mao's speech from atop Tiananmen gate on October ane, 1949, announcing the formation of the People's Republic of China (PRC), augured a bright Communist future for the Chinese people who had suffered decades of warfare, runaway inflation, and misgovernment. Whereas the previous Guomindang (GMD) government of Chiang Kai-shek had rested on the support of Chinese elites, Mao implemented, on a national scale, policies that fabricated him popular among the masses, including reducing rents and redistributing land to farmers in the countryside. The reorganization of Chinese gild nether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) necessitated the classification of China's vast population into discrete groups such as peasants, landlords, laborers, capitalists, etc., followed by the issuance of registration cards and assignment to a danwei, or work unit. These measures served as the mechanism for state oversight of everything from food rations to housing to marriage, while at the same fourth dimension ensuring complicity with state directives and mobilization for mass political campaigns. Initially, these mass campaigns were aimed at—and effectively combated—social vices such as opium addiction and prostitution, but soon, campaigns targeted enemies of the revolution and, during the Korean War (1950–1953), the party galvanized the population to protect its North Korean marry against the American-led United nations. These successes bolstered religion in the party and primed the Chinese population for supporting radical programs that promised to raise Prc from the feudal to the Socialist, and eventually Communist, stages of social evolution.

Despite the disastrous Soviet experiment with collectivization and increasing grumbling from China'due south population, domestic and international events steeled Mao's resolve to surge ahead with the 2d 5 Year Program, also known equally the Great Leap Forrad.

Collectivization

After the Korean War, the Chinese authorities turned single-mindedly to realizing socialism through domestic evolution on two fronts—industrialization in cities and collectivization in the country- side. For this, the Chinese modeled their arroyo on the Five Year Plans employed by the Soviet Marriage since 1928—a tragic irony given that forced collectivization under the Soviets had resulted in the starvation of between six to viii million people. Notwithstanding, China's showtime Five Year Plan initially saw nifty success through investment in land-owned factories that produced such things as tractors, mechanism, and chemic fertilizer with aid from Soviet planners. Payment for urban evolution would come from China's countryside, where some 75 percent of the population lived and where the land began collectivization of agriculture. Although the government had recently confiscated land from landlords and redistributed it to farmers, collectivization now pooled land and resources for efficiency. Vast communal fields were far more conducive to mechanized farming than millions of small, family unit-sized plots. The cease goal of collectivization was abolishment of individual buying, or Communism, with its anticipated shared prosperity.

Collectivization proceeded in stages, get-go with possibly x families voluntarily cooperating in common aid teams (MAT). In this early phase of socialism, each family unit agreed to share their labor, tools, and draft animals with other squad members while retaining buying—a human relationship that had historically existed inside farming communities but was at present formalized past contract. The formation of low-level agronomical producer'southward cooperatives (APC) was the next stride. Five teams or 50 households comprised an APC, and each contributed their resource, including state, to the cooperative. Families retained championship to their packet of state and were compensated based on their contributions of country and labor. As these moderate steps toward collectivization proved effective, by tardily 1955 Mao moved to the side by side—and more controversial—phase by combining approximately five depression-level cooperatives into higher-level cooperatives, encompassing some 250 households each. Private property was abolished as country; animals, tools, or other resource became holding of the cooperative; and labor became the sole criterion for compensation.

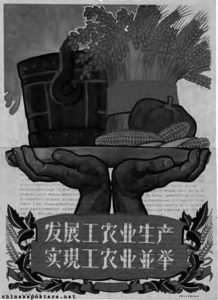

industrial and agricultural product, realize the simultaneous evolution of manufacture and agriculture . . ."

Source: http://tiny.cc/ufphmw.

The beginning Five Twelvemonth Plan yielded impressive results. China's overall economy had expanded about 9 percent per twelvemonth, with agricultural output ascension about 4 percent annually and industrial output exploding to but shy of 19 percent per year. More important, life expectancy was xx years longer in 1957 than when the Communists took power in 1949.1 Just as collectivization entered a more than radical phase, problems became apparent. Impressive industrial output statistics yet, quantity took precedence over quality, and quota requirements often resulted in shoddy final products. Also, rural people resisted private holding confiscation. Despite the disastrous Soviet experiment with collectivization and increasing grumbling from Mainland china's population, domestic and international events steeled Mao's resolve to surge alee with the 2nd Five Year Plan, also known as the Great Jump Forrard.

A Hundred Flowers Bloom

In early 1956, as the offset Five Year Programme reached loftier tide, the party, flush with success, invited comments from Chinese intellectuals and the public in a directive known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign, a metaphor equating contending ideas with blooming flowers. Initially hesitant to speak out, start scientists and then literary figures, students, and common people voiced criticisms of party policies. This was not only tolerated but encouraged until two international events reversed Mao'south openness. The first was Nikita Khruschev's shocking denunciation of Stalin, his own predecessor, who had died three years before. The attack on Stalin'due south collectivization policies and subsequent de-Stalinization of the Soviet Spousal relationship served as a cautionary tale for Mao, who found himself increasingly embattled within the CCP. And then, inspired by the criticisms of Stalin, Hungarians revolted against the Soviet Union in October 1956. Moscow brutally suppressed the rebellion, and when his compatriots began public attacks against him, Mao reverted to Soviet tactics.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign

On June 8, 1957, the party appear the existence of a nationwide anti-Communist plot and warned that approximately 5 percent of the population was even so comprised of "rightists"—that is, political conservatives sabotaging the revolution. In response, local cadres felt compelled to identify which five percent within their ranks were rightists. Half a million or more were branded with the label "rightist," which went in their permanent record, ruined their careers, made them social pariahs, and, for many, exiled them to labor camps or drove them to suicide. Their labels, or "caps," would non exist re- moved until the blanket rehabilitation in 1979, three years afterwards Mao's death. In addition to removing the most educated from society, the Anti-Rightist Campaign discouraged the Chinese people from voicing any doubts or criticisms and left them amenable to even the most irrational and misguided policies, including the cool notion that economic development required merely ideological correctness, non scientific or technical expertise.

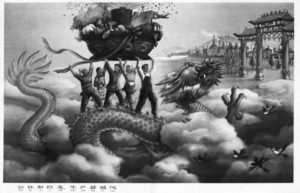

One of the most infamous innovations of the Great Jump involved an industrial revolution in the countryside. . .

A Slap-up Leap

In 1958, Mao launched the 2nd V Year Plan, dubbed the Great Bound Forwards. The movement bore his characteristic faith in China'due south bucolic masses—now unfettered by skeptical intellectuals—to surmount any obstacles and accomplish a Communist utopia through unity, physical labor, and sheer willpower. In this final stage of collectivization, communes formed—each with some v,500 house- holds, more than twenty times larger than previous cooperatives. Communes would be self-sufficient in agriculture, industry, governance, pedagogy, and health care. The commune would guarantee to each private a gear up income, regardless of labor contributions, just in the spirit of wild optimism that prevailed at the fourth dimension, most rural Chinese threw themselves wholeheartedly into the Not bad Jump. Farmers worked in the fields all day and sometimes into the night, a do known as "communicable the moon and stars," all the while shouting slogans to sustain their enthusiasm.ii At night, many did non bother returning home, opting instead to join other members of the district, sleeping in makeshift sheds in the fields. Kitchens allowed a designated chef to feed the entire commune from huge pots, which were sometimes located in the fields to avoid wasted travel fourth dimension. When compared with the traditional family meals, this system offered more efficient resource utilise and freed mothers to piece of work aslope the men. For the same reason, families placed infants in communal nurseries while the elderly and in- firm spent their days in "happiness homes," all moves calculated to impose greater equality, free up laborers, and maximize production.

Although an adequate food supply was necessary, the existent gauge of development was steel. Imagine if China'south hundreds of millions of farmers could also contribute to industrial development! 1 of the well-nigh infamous innovations of the Great Leap involved an industrial revolution in the countryside, where farmers constructed millions of backyard furnaces and then divided their time betwixt disposed crops and smelting steel. Gathering fuel to stoke all these furnaces resulted in the loss of at least ten percent of China's forests, and when wood became increasingly scarce, peasants resorted to burning their doors, furniture, and even raiding cemeteries for coffins.iii Rather than mining the ore to exist smelted, anybody contributed iron implements, including tools, utensils, woks, doorknobs, shovels, window frames, and other everyday items, while children scoured the basis for iron nails and other scraps. Farmers had no technical expertise in smelting steel, of course, but these skills were derided equally bourgeoisie and rightist anyway. Unsurprisingly, the campaign essentially converted applied items into useless lumps of pig iron skillful only for clogging railroad yards. As a attestation to the growing disparity between reality and farce, Mao projected that past the end of the Nifty Jump Forward in 1962, China would exist the world'south leading steel manufacturer with 100 meg tons, outproducing fifty-fifty the United states.iv That would exist an increase of ii,000 percent in v years, clearly an impossibility.

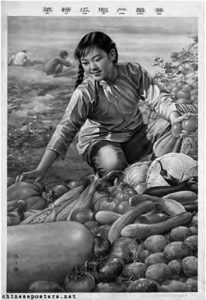

miraculous prosperity during the corking Leap Frontwards, equally suggested past the image. Source: http://tiny.cc/9uphmw.

At the same fourth dimension that farmers became the courage of industrial production, urban cadres fabricated command decisions for the nation's agricultural output to similar effect. They too set up unrealistic quotas but likewise distributed pamphlets to farmers mandating the employ of multiple harvests, over seeding, deep ploughing, and over fertilizing.5 Although farmers knew better and did not always implement the suggestions, some were compelled to practice such things as dig a pigsty the size of a pond puddle and pour in all their seed grain in expectation of a phenomenal ingather or break up clay pots and work them into the soil—even though the nutrients had been baked out.vi Ignorance at the centre was met by fanatical devotion to Mao'due south vision and an intense competition amidst communes—"if a neighboring commune projected a doubling of grain output, then certainly our commune can produce triple." And merely as those with the greatest faith were the most "red," anyone who questioned fifty-fifty the most unrealistic goals became a rightist. Recalling the consequences of the Anti-Rightist Campaign a year earlier, local leaders felt compelled to see ridiculous grain quotas at any price or, more often, to falsify their reports. Whether out of ignorance or fear, those in the party'due south highest ranks tended non to question the exaggerated figures, and fifty-fifty when Mao did visit the countryside to investigate, the locals intentionally transplanted crops forth his road to give the illusion of wildly dense yields.seven This "evidence" only encouraged flights of fancy.

When authorities uncritically accepted and publicized inflated production figures, the Great Leap Forrad appeared a spectacular success. The New China News Agency carried stories and photos of fields that grew so dense equally to back up the weight of children and of supersized fruits and vegetables, similar a 132- pound pumpkin and a giant radish being paraded through the commune past truck or on a palanquin.eight Accepting the stories at face up value, survivors recall gorging themselves in eating contests and neglecting their crops, and communal kitchens dumped leftovers from each meal. The People's Daily debated how Communist china should deal with its new surplus, and in the end, the country increased grain exports, replaced some food crops with greenbacks crops like cotton or tea, and raised the charge per unit of tax extracted from communes from xx to 28 per centum, despite the fact that from 1958 to 1960 overall grain production actually fell 30 percent. 9

The Lushan Conference

All these trends indicated pending catastrophe, so why did no one speak out? Every bit the disaster began to unfold in 1959, the party held a height at the mountain resort of Lushan. There, Peng Dehuai, minister of defence and longtime associate of Mao, privately handed the chairman a handwritten letter.

In information technology, he first recounted their successes, simply confessed that in an unprecedented undertaking such as the Bully Leap Forward, mistakes were unavoidable due to inexperience. He warned of exaggerations, waste, and fanaticism merely carefully avoided blaming whatever individual and even implied that he and others had failed to follow Mao's wise admonitions. He concluded that they should acquire from their mistakes past undertaking "an earnest analysis."x Despite the deferential wording, Mao interpreted the note every bit a personal attack and convened the top party leadership, forcing those nowadays to choose betwixt himself and Peng.11 The political party voted to characterization Peng a rightist, and he spent the residuum of the Great Jump under business firm abort. Every bit with the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the bulletin was clear—Mao brooked no criticism, and the Great Leap would continue.

As food reserves in the countryside diminished, peasants began dying in droves by the summer of 1960.

Famine

Starvation became a widespread problem with the harvest of 1959. The government had raised the tax rate to 28 percent, but because local leaders had inflated the production figures on which the taxes were based, the state really appropriated a much higher percentage of their grain. The worse the exaggeration, the greater the amount of taxes taken; some regions forwarded well-nigh their entire crop to the state as tax, leaving nothing on which the farmers who actually grew the food could subsist. Even when some fell short in their revenue enhancement obligation, leaders who had falsified reports refused to admit the error and in some cases even accused the farmers of hiding grain—for which they were hunted, beaten, and tortured by their own neighbors. In reality, the appropriated grain sat in state warehouses or made its mode to the cities where rations were cut (Mao supposedly went without meat for seven months). Undernourishment grew amid the urban population and, with it, cases of edema and other maladies, just urbanites fared insufficiently well.

As food reserves in the countryside diminished, peasants began dying in droves by the summer of 1960. They collapsed in fields, on roadsides, and fifty-fifty at home where family unit members watched their corpses rot, lacking the energy for burying or even to shoo away flies and rats. Some families would hide the remains of relatives in the home and then that the living could collect the food rations of the deceased. Hunger drove the starving to provender for seeds, grasses, leaves, and tree bark, and when even these became scarce, they boiled leather or ate soil just to fill their stomachs, fifty-fifty when information technology destroyed their digestive tracts. Given the prevalence of hunger and exposed corpses, some inevitably turned to cannibalism. Although this involved scavenging for the most part, occasionally persons—commonly children—were intentionally killed as food.12 Rarely did this happen within a family, but stories are told of villagers exchanging their babies to avert consuming their own flesh and blood.thirteen

Although tales of famine were leaking out of Cathay, Western scholars had little sense of the scale of the disaster. In his study on agricultural evolution in China that included the Keen Leap Forward, Harvard sinologist Dwight Perkins asserted that the government had avoided disaster and that "few if any starved outright."14 It was non until the postal service-Mao government that demographers began to put the picture together. Estimates of deaths straight related to the famine range from a minimum of twenty-three million to as many as fifty-five one thousand thousand, although the figure virtually often cited is thirty million.15 While there is bear witness to suggest that farthermost atmospheric condition—backlog rain in the south and drought in the n— may have exacerbated the problem, weather became a convenient scapegoat, along with the GMD and the Soviets. 16 When Sino-Soviet relations deteriorated during the Great Leap, Soviet advisors were re- chosen from China, and the Soviets chosen in Chinese debts that supposedly caused the hardship. In some cases, peasants blamed either the GMD or their local village leader but seldom Chairman Mao or the Communist Party.17 This is however the example in China'southward textbooks and commonage memory.

Estimates of deaths directly related to the famine range from a minimum of 20- 3 million to as many as fifty-five million, although the figure most often cited is 30 1000000.

Determination

The Chinese have always faced famine. According to 1 report, China experienced some 1,828 major famines in its long history, simply what distinguishes the Great Leap Forwards from its predecessors are its crusade, massive telescopic, and ongoing concealment. In his recent study of famine, Cormac Ó Gráda suggests that, historically, famines emerged from natural phenomena, sometimes exacerbated by homo activity. Modern famines, on the other hand, stem from human factors such as war or ideology exacerbated by natural conditions.18 In this sense, the Nifty Jump Forward stands out as uniquely modernistic. Although previous famines affected dissimilar regions for different reasons, the Great Leap Frontwards affected every role of People's republic of china, some places worse than others, just for the start time in China's history, migrating to another region was forbidden and probably of piddling employ anyway. Almost tragically, the subsequent purging of Peachy Leap excesses from history and the unspoken taboo that continues to environment it have prevented the Chinese from reflecting on and learning from this outcome, even as it remains largely ignored exterior of China. While doubtless many lessons could be derived from the Great Leap Forward, it possibly stands above all equally a testament to the value of independent thought and gratuitous spoken communication. The worst peacetime famines of the modernistic era not-coincidentally occurred under totalitarian regimes, such equally the Soviet Spousal relationship in 1932–33, with an estimated half-dozen million dead; the Cracking Bound Forward in China 1960–62, with some thirty million dead; and Democratic people's republic of korea in 1995, which, like the Great Leap, killed around 5 per centum of the population. On the other hand, evidence confirms that "famines are very much the exception in democracies," and it is speculated that the overall fall in famine mortality over the past century is due to the growth of republic across the globe, both in terms of relative prosperity and humanitarian help.nineteen The benefits of an open up, pluralistic social club where criticisms of policy and authority are tolerated is a valuable lesson for Chinese—or American students, for that matter—to learn.

NOTES

- Keith Schoppa, Revolution and Its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010), 318.

- China: A Century of Revolution, Part two, "The Mao Years," YouTube video, 114 minutes, http://tiny.cc/zarhmw.

- Judith Shapiro, Mao's War Against Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001),

- Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, 2: The Great Leap Forward, 1958-1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 90. Today, China does indeed lead the world in steel production, only the transition from net importer to exporter of steel occurred only in 2004, nearly one-half a century after the Great Leap Forrard. Come across "Special Report: China's Economic system," The Economist 403, no. 8786 (May 26, 2012): 6.

- Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (New York: Touchstone, 2003), 225; Jasper Becker, Hungry Ghosts (New York: The Complimentary Press, 1996), 70–77.

- From farmers' recollections in China: A Century of Revolution, Part 2, "The Mao Years" and Peter Seybolt, Throw- ing the Emperor from His Horse (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), 52–58.

- Becker, 72; Li Zhisui, The Individual Life of Chairman Mao (New York: Random House, 1994),

- Chang, 225–six; Becker,

- Becker, 79, 81; Cormac Ó Gráda, Famine: A Short History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 242,

- Patricia Ebrey, Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook (New York: The Free Printing, 1993), 435–39.

- A firsthand account of the meeting is given in Li Rui, A True Account of the Lushan Meeting (Henan: Henan People'due south Publishing House, 1994).

- See Frank Dikötter, Mao's Great Famine (New York: Walker and Company, 2010), 320–23 and Becker, 118–xix.

- Wei Jingsheng, The Courage to Stand Alone (New York: Viking, 1997), 246–47.

- Dwight Perkins, Agricultural Evolution in Red china, 1368–1968 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1969), 303–19.

- Dikötter, 324–34.

- Dissimilar perspectives on the role nature played in the famine are surveyed in Ó Gráda, 247–49.

- Chang,

- Ó Gráda, 9–10.

- Ibid., 13, and chapter 8 on "The Violence of Regime."

lawrenceglact1990.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

0 Response to "during the “great leap forward,†what were peasants encouraged to produce in their backyards?"

Post a Comment